The Economy of Ego and the Real Price of Hosting the Olympics

This summer, Paris 2024 made a lot of headlines for its record-breaking ticket sales, selling over 12 million tickets from the combined Olympics and Paralympics games, full-gender parity on the field of play with equal male and female athletes, and hosting the opening ceremony outside of a stadium for the first time in modern Olympic history, with athletes paraded by boat along the Seine. What not a lot of people know is that Paris 2024 is also the first manifestation of the Olympics Agenda 2020, a reformation plan by the International Olympics Committee (IOC) to make the Games friendlier to the economy and the environment, following decades of debates over the costs and benefits of hosting these mega-events.

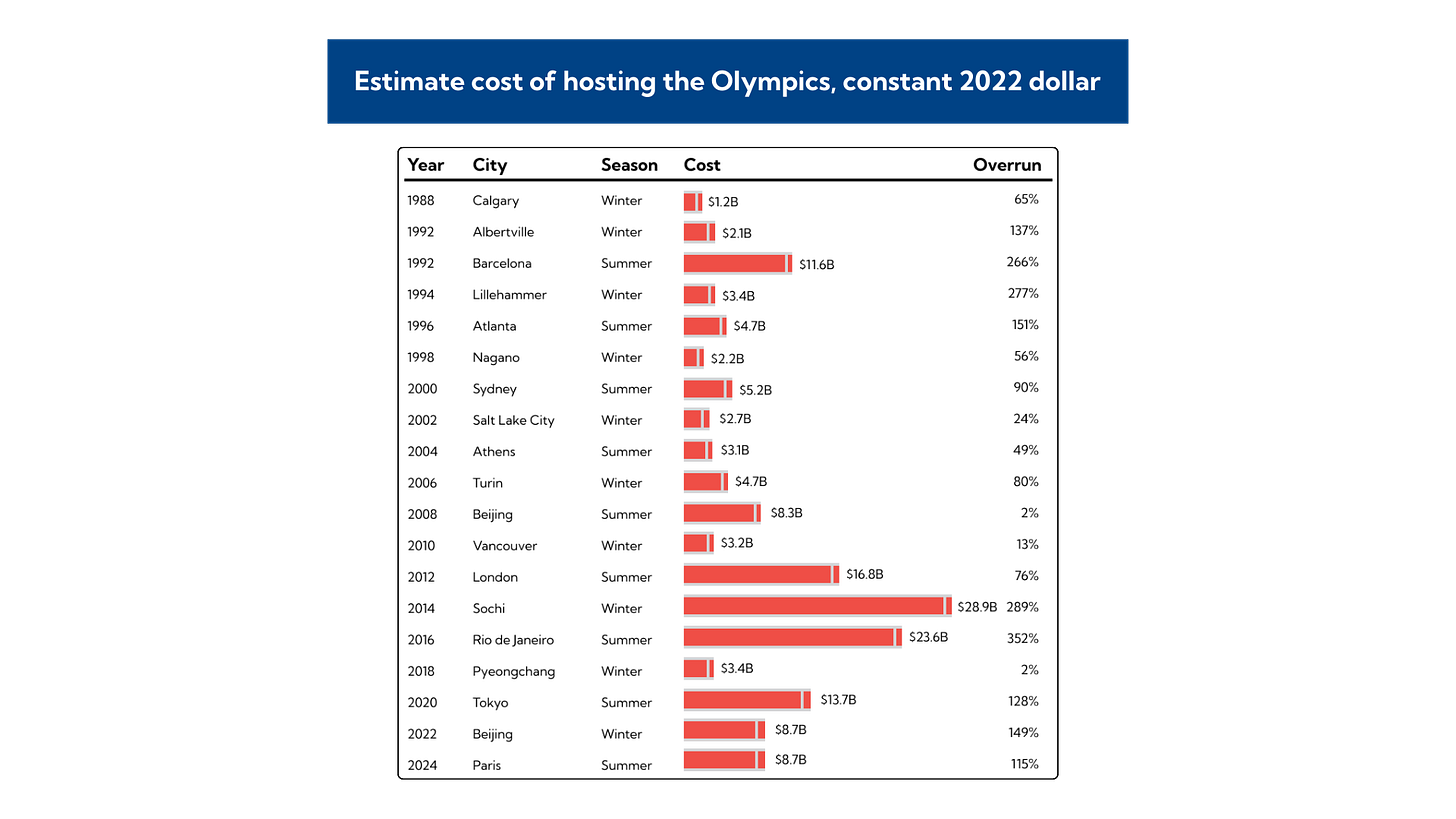

As the costs of hosting have grown rapidly compared to the revenue produced by the spectacle, sparking controversy over the burdens host countries shouldered, a growing number of economists have argued that the benefits of hosting the games are at best exaggerated and at worst non-existent, leaving many host countries with large debts and maintenance liabilities.

When did the costs of hosting the games start becoming a concern?

For much of the twentieth century, hosting the Olympic Games was a manageable responsibility for cities, typically taking place in affluent countries, mainly in Europe or the United States, which had the economic strength and infrastructure to handle the expenses. Before the advent of television broadcasting, these host nations did not anticipate making a profit from the Games.

But in 1972, Denver marked a turning point when it became the first and only chosen host city to reject the opportunity to host after voters passed a referendum refusing additional public spending for the games. The 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal came to symbolize the fiscal risks of hosting with the city spending billions more than the projected cost of $124 million, primarily due to construction delays and cost overruns for the stadium, saddling taxpayers with $1.5 billion in debt that took nearly three decades to pay off.

Los Angeles was the only city to bid for the 1984 Summer Olympics, allowing it to negotiate exceptionally favourable terms with the IOC and thus becoming the only city to turn a profit hosting the Olympics, finishing with a $215 million operating surplus. They profited from the sharp jump in revenue from television broadcasting and significantly minimized costs by relying almost entirely on existing stadiums and infrastructure.

Los Angeles’ success led to an influx in bidding cities—from two for the 1988 games to twelve for the 2004 games—and bidding by developing countries more than tripled after 1988. However, these countries invested massive sums to create the necessary infrastructure. Since then, costs have spiralled to over $50 billion for the 2014 Winter Games in Sochi, $20 billion for 2016 Summer Games in Rio de Janeiro, and $43 billion for the 2022 Winter Games in Beijing.

What expenses do host cities incur when hosting the games?

Prior to hosting a game, cities need to invest millions of dollars just to submit a bid to the IOC. The cost of planning, hiring consultants, organizing events, and the necessary travel consistently falls between $50 to $100 million. Tokyo spent as much as $150 million on its failed 2016 bid, and about half that much for its successful 2020 bid, while Toronto decided it could not afford the $60 million it would have needed for a 2024 bid.

Once a city is selected, it has about a decade to prepare for the arrival of athletes and tourists. The Summer Games are significantly larger, attracting hundreds of thousands of international visitors and featuring over 10,000 athletes competing in nearly 300 events, compared to the Winter Games, which host fewer than 3,000 athletes in around 100 events. Key priorities include building or upgrading specialized sports facilities like cycling tracks and ski-jumping arenas, as well as creating an Olympic Village and a venue for the opening and closing ceremonies.

Beyond sports facilities, host cities also need to enhance their general infrastructure, particularly housing and transportation. The IOC mandates a minimum of 40,000 hotel rooms for cities hosting the Summer Games, necessitating upgrades or new construction for roads, railways, and airports. Overall, infrastructure costs can range from $5 billion to over $50 billion, with many countries hoping that these investments will yield long-term benefits.

Operational costs, though smaller, are still a significant portion of a host city's Olympic budget. Since the 9/11 attacks, security expenses have surged. For instance, Sydney allocated $250 million in 2000, while Athens’ costs soared to over $1.5 billion in 2004, with ongoing expenses typically between $1 billion and $2 billion. During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2022, Tokyo reportedly spent $2.8 billion solely on health precautions.

Additionally, the long-term maintenance of these expensive facilities poses ongoing financial challenges. Many venues, due to their size and specialized nature, see limited use post-Games, leading to significant maintenance costs. Sydney’s Olympic stadium costs the city $30 million annually, while Beijing’s "Bird’s Nest" stadium, built for $460 million, requires $10 million a year to maintain and has seen limited use since the 2008 Games, aside from the 2022 Winter Games. Most facilities from the 2004 Athens Olympics now stand in disrepair, contributing to Greece's debt crisis. Montreal’s Olympic stadium, often referred to as the "Big Owe," is infamous for its costs; in 2024, Quebec's government allocated $870 million for a third roof replacement, prompting calls for its demolition.

Economists argue that the implicit costs of hosting the Games must also be considered, including the opportunity costs of public funds that could have addressed other priorities. The lingering debt from the Olympics can burden public budgets for decades. For example, Montreal took until 2006 to pay off its debts from the 1976 Games, while Greece's billions in Olympic-related debt contributed to its bankruptcy.

The financial fallout from the Sochi 2014 Winter Games is expected to cost Russian taxpayers nearly $1 billion annually for the foreseeable future. While some residents view the unused facilities as wasteful, others argue that the Games prompted essential investments in roads, water systems, and public amenities.

In Brazil, the first South American nation to host the Olympics, the 2016 Games exceeded $20 billion in costs, with Rio de Janeiro alone responsible for at least $13 billion. Facing a severe recession, Rio required a $900 million federal bailout to cover Olympic policing costs and struggled to pay public employees. Despite the intention to revitalize struggling neighbourhoods, many venues have since been abandoned or underutilized.

The delayed Tokyo 2020 Games, impacted by pandemic restrictions, eliminated spectator attendance, resulting in an estimated $800 million loss in ticket sales and significant hotel cancellations. Ultimately, hosting the Games cost around $13 billion—more than double initial projections from when Japan won the bid in 2013. Economists suggest that this figure omits land and transportation costs, with the true total likely between $19 billion and $34 billion. New venues, such as the $1.4 billion National Stadium, sat empty during the Games, prompting Tokyo to plan for the stadium’s privatization in 2025 by selling operational rights for thirty years in exchange for just a quarter of construction costs.

Given these soaring costs, how do the benefits measure up?

Revenues from hosting the Olympics cover only a small fraction of expenditures. For instance, Beijing’s 2008 Summer Olympics generated $3.6 billion against costs exceeding $40 billion, while Tokyo’s 2020 Games brought in $5.8 billion compared to their $13 billion cost. It’s important to note that a significant portion of the revenue does not go to the host city, as the IOC retains over half of all television revenue, which is typically the largest source of income from the Games.

Impact studies conducted by host governments often claim that the Olympics will provide a substantial economic boost through job creation, increased tourism, and enhanced overall economic output. However, evidence supporting these claims is limited, and post-Games research frequently casts doubt on these benefits. Jobs created during Olympic construction are often temporary, and in regions not experiencing high unemployment, they typically go to workers already employed.

The impact on tourism is similarly mixed. The security measures, crowding, and higher prices associated with the Olympics can deter visitors. While the Barcelona’s 1992 Olympics is often hailed as a tourism success—rising from the eleventh to the sixth most popular European destination—other cities like Beijing, London, and Salt Lake City experienced declines in tourism during their respective Games.

What did the 2024 Paris Olympics do differently?

Paris 2024 was arguably the cheapest Summer Games in decades. Paris spent around $10 billion for the 2024 Olympics–roughly 25% over the initial budget of $8.2 billion they submitted when they won their bid in 2017. Costs are split relatively evenly between operating expenses and new infrastructure, according to an S&P Global Ratings analysis.

To lower the chances of debt and keep up with sustainability goals, 95% of the facilities used were existing or temporary. Organizers say the decision to rely almost entirely on existing venues, such as those built for the annual French Open and the 2016 European Football Championship, has held down costs. The games were spread out in stadiums in other French cities, including Lyon, Marseille, and Nice. They also increased efforts to minimize the carbon footprint of the games, relying on low-impact or recycled goods whenever possible — such as furniture made with shuttlecocks — and identifying second lives for the temporary structures and equipment utilized for the games.

A notable change to the city was Mayor Anne Hidalgo’s successful efforts in decontaminating the River Seine, which was in use for the hosting the opening ceremony. Athletes paraded down the already in-place structure, rather than building a new venue.

But Paris still spent over $4.5 billion on infrastructure, including $1.6 billion for its Olympic Village, whose price is at least one-third more than it originally budgeted. The Olympic Village is an unavoidable cost. This year, it stretches across three cities - Saint-Denis, Saint-Ouen-sur-Seine, and L'Île-Saint-Denis - and will be turned into housing and office spaces with amenities in historically impoverished neighbourhoods following the games.

What steps can be taken to make the Olympics more manageable?

Economists increasingly agree that the IOC bidding process for the Olympic Games promotes wasteful spending by favoring hosts with the most ambitious plans. This so-called winner’s curse means that over-inflated bids—often pushed by local construction and hospitality interests—consistently overshoot the actual value of hosting. Observers have also criticized the IOC for not sharing more of the fast-growing revenue generated by the games. Corruption and bribery scandals have also marred the 1998 Nagano and 2002 Salt Lake City games. In 2017, the head of Rio’s Olympic committee was charged with corruption for allegedly making payments to secure the Brazil games, and allegations of illegal payments also resurfaced in the 2020 Tokyo selection.

The IOC is using its Olympic Agenda 2020 to reform the process, aiming to reduce the cost of bidding, allow hosts more flexibility in using already-existing sports facilities, encourage bidders to develop a sustainable strategy, and increase outside auditing and other transparency measures.

However, many thinks drastic measures are necessary. Economists Baumann and Matheson argue that low- and middle-income countries should spare themselves the burden of hosting altogether. Economists Andrew Zimbalist has proposed that one city be made the permanent host, allowing for the reuse of expensive infrastructure. The original home of the Olympics in Greece is sometimes proposed. Ultimately, many economists argue, any city planning to host should ensure that the games fit into a broader strategy to promote development that will outlive the Olympic festivities.

If the Olympic Games tend to offer only a low chance of providing host cities with positive net benefits, why do cities keep lining up to host these events? It seems that economic concerns only play a small role in a country’s decision whether or not to stage the Olympics. The desire to host the Games is often more driven by the ambitions of a country’s leaders or as a demonstration of a country’s political and economic power.

In line with this concept, President Joko Widodo has expressed interest and readiness for Indonesia to host the 2036 Olympics in the new capital Nusantara, which is being developed to replace Jakarta as the country’s administrative capital and is slated to be fully completed in 2045. This ambition has been further reiterated during a meeting between President-elect Prabowo Subianto and IOC President Thomas Bach during the Paris 2024 Olympics. If successful, Indonesia will become the first country in Southeast Asia and the third country in Asia to host the Olympics.